Innovation:The Heart of Urban Ag Science at Hoboken Charter School Upper

GUEST POST BY ARTHUR EVES, HOBOKEN CHARTER SCHOOL

When Arthur Eves joined the Hoboken Charter School staff his passion for urban agriculture was just an idea. With the support of the school’s administration, colleagues, and most importantly, student interest, urban agriculture has become a reality in this project-based science lab, made possible by the innovative curriculum provided within the charter model.

Urban Agriculture may sound like an oxymoron but Hoboken Charter’s Upper School students have turned it into a synonym for activist science and engineering. The school’s mission is to develop the individual students with a focus on civic growth through service learning and real-world applications. Urban Agriculture is a project-based elective driven by student interests. As a co-teacher with Sean Maurizi, our role is to assess and align student interests with the curriculum, give guidance, provide tools and materials needed and supervise to ensure every student is safe. The students own the project, make the plans, do the work, make mistakes and identify them, problem-solve, and create something of lasting value.

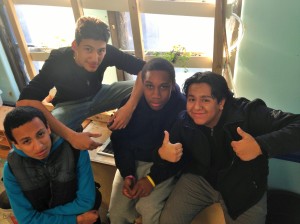

The gutter garden is a good example of how the project-based learning process works. In Urban Agriculture, one team of students, Luke Aranibar, Angel Lebron, Chris Cobb, and Moroni Aranda (pictured, l-r), recently addressed the need for urban farming and giving back to the Hoboken community through the completion of an aquaponic recirculating system that takes dirty water from our fish/turtle tank and pumps it up to a vertical gutter garden where the water is cleaned by a biological filter: the sweet potatoes, peas, parsley, beans, and tomatoes that we are growing.

The project started when we assessed some of the problems and some of the opportunities our classroom presented. The turtle tank was a big stinking problem if the water wasn’t changed on a semi-daily basis, which required manpower and a lot of water. Not to mention, we have lots of afternoon sun, which makes PowerPoint presentations difficult—not to mention, disengaging. So, with my colleague Sean Maurizi, we pitched this project to students and a small team jumped on it. We had them do research and create a design, which they needed to “pitch” to Sean and I for approval. Based on their design, I bought and salvaged materials and the kids went to work on constructing the garden—packing materials were repurposed to hold water but keep loads light on the gutters; students sawed, hammered, and tested prototypes, and soon enough we were ready to transplant the vegetables.

The garden has been up and running for a few weeks, we’ll be experimenting with various factors: evaluating water flow and drying cycles, testing different plants, adding more fish to the tank, and testing the garden’s ability to eat up nutrients and toxins. In the first weeks it has done a fabulous job of cleaning the turtle water which now is clear no matter how much we feed them. The real test was how it would fare without daily check-in over winter break and the result when we returned was a thriving ecosystem conceived and built by the four students.

We’re hoping to build on this small success with two more projects that are in the early stages of development. We hope to partner with the City of Hoboken and a local food pantry to significantly expand our community garden, make it a demonstration area with exhibits for the public, and donate the vegetables and greens to local food groups. Another project will work with people at the senior center to develop a small pocket garden there to serve the community.

Elsewhere in the classroom we have students creating an urban fashion business, a mural, and some experimental “living walls” are slowly emerging. It is incredibly meaningful and important work to see my students tackle sustainability issues, and create real solutions to real world problems—our world needs more of these problem-solving minds, and I’m grateful to have the opportunity to guide them.

Arthur Eves is a science teacher at Hoboken Charter School Upper who was called to the teaching profession six years ago by a vague vision about giving urban youth tools that might help them transform their environments in meaningful ways. Mr. Eves is also an island naturalist at Star Island, a retreat center off the coast of New Hampshire, where he brings a group of students each year. It is his dream come true to guide students in their discovery and creation of sustainability systems for the environment.